Alexander Zaitsev: The Genius from Vladivostok

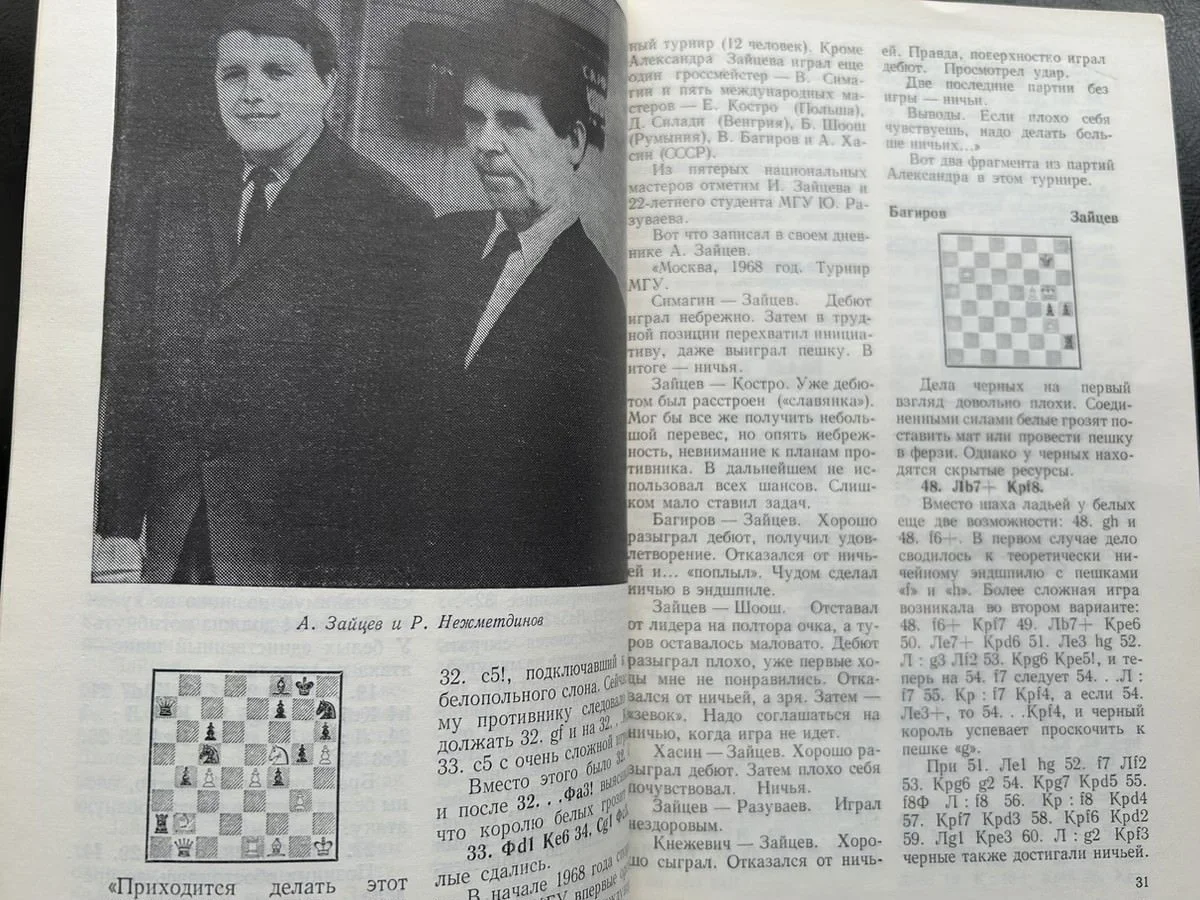

Alexander Nikolayevich Zaitsev (1935–1971) occupies a rare place in Soviet chess history. His career was short, intense, and brilliant, the kind that leaves behind a small body of games but an outsized reverence among those who knew him. Within the Soviet chess world, he was spoken of as a creative force, a daring analyst, a man whose ideas were original enough to unsettle even elite grandmasters. To players like Mikhail Tal, Boris Spassky, and Vladimir Simagin, Zaitsev was not simply a master; he was one of those rare spirits who thought differently about the board. “His play was never routine… every stage of the game was interesting,” Tal once said, praising how Zaitsev’s games were “far from [the] clichés” of ordinary chess.

And yet, like several great Soviet talents, Zaitsev lived far from the centers of chess power. Raised and developed in Vladivostok, practically the edge of the chess world, he built himself into a grandmaster largely through solitary study, correspondence games, and an inner drive stronger than any formal institution. His story is one of brilliance forged in isolation: a mind that thrived on complexity, and a life cut tragically short just as he reached his prime.

A Talent Born at the Edge of the Map

Zaitsev’s journey began far from Moscow’s famous clubs or Leningrad’s legendary schools. Born in 1935 in Vladivostok, he was one of the few prominent Soviet chess figures raised in the Far East, an area where intense competition was scarce and a young player’s ambition required exceptional self-reliance. He only learned the rules of chess at 14 years old, getting a chess set as a birthday gift, and with virtually no local masters to guide him, he turned obsessively to books, magazines, and notebooks of analysis. Zaitsev would study positions for hours on end, often deep into the night. As a teenager, he reconstructed classical games from literature and challenged stronger players through correspondence play. His extraordinary work ethic, spending 8 to 14 hours per day on chess study, bordered on obsession. This relentless self-training paid off: within just a few years, he progressed from novice to first-category strength by age 18, an impressive local feat for someone with no strong sparring partners.

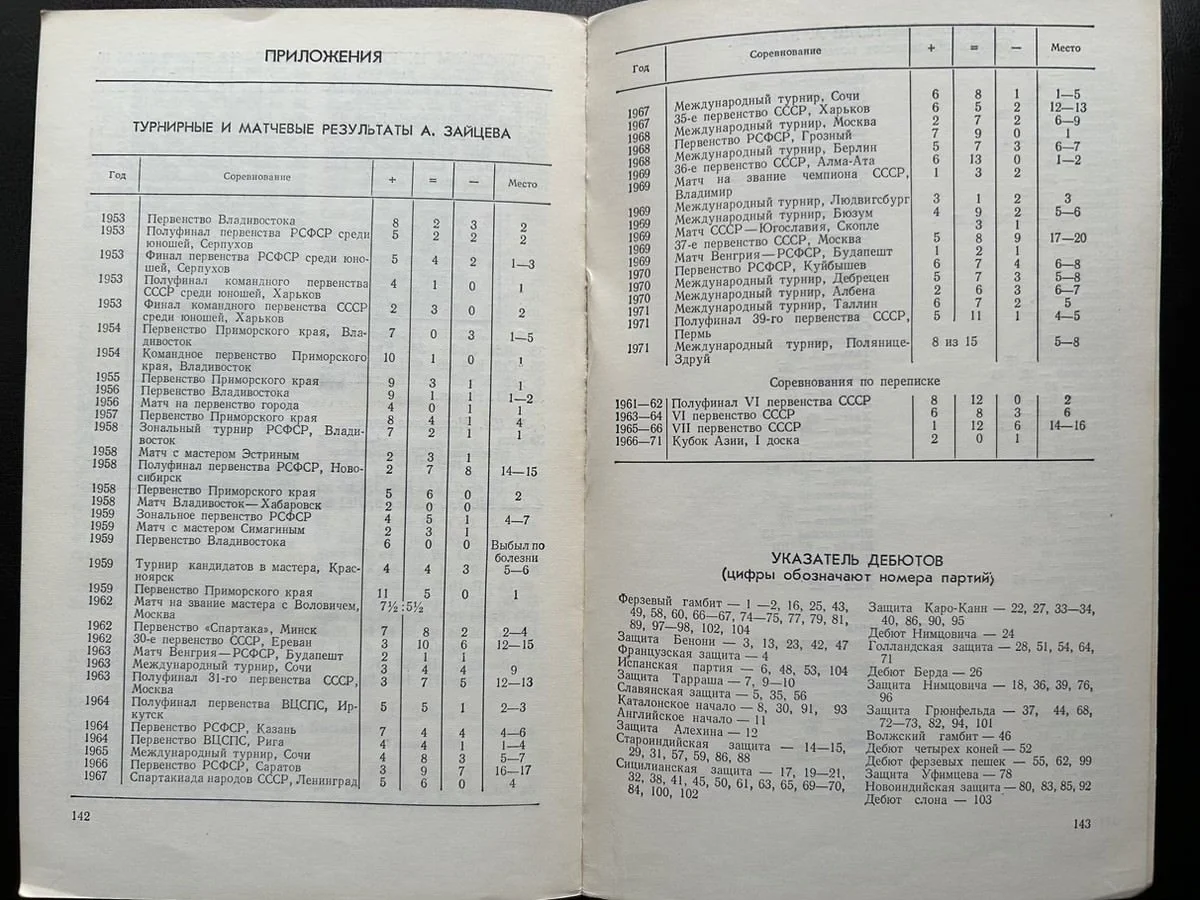

By the early 1950s, Zaitsev had become the dominant youth talent of his region. In 1953, only four years after he began playing seriously, the 18-year-old tied for first (1st–3rd place) in the Russian Federation (RSFSR) junior championship. He repeatedly won the regional titles in Primorsky Krai (Far East) throughout the mid-1950s. Then, in 1958, came the breakthrough that put him on the national radar: Zaitsev took first place in a combined Siberia Far East zonal tournament, a competition of the best players in Asiatic Russia. This victory was the turning point of his career and proved that a world-class talent was emerging from the country’s distant edge.

From Isolation to the Soviet Elite

Zaitsev’s true breakthrough on the bigger stage came in the early 1960s. In 1962, he earned the title of Soviet Master of Sport and qualified for the finals of the USSR Championship, an enormous achievement for someone who had grown up thousands of kilometers from the Soviet chess heartland. However, his debut in the 30th USSR Championship (Yerevan 1962) exposed a major flaw in his play: he played far too quickly. Unaccustomed to long over-the-board battles, Zaitsev often spent only a fraction of his allotted time. He would sometimes use barely half (or even a third) of the clock time his opponents used, leading to unnecessary errors in simpler positions. Soviet commentators half-jokingly chided that he was treating classical games like five-minute blitz.

Fortunately, Zaitsev soon came under the wing of the experienced Georgian coach Vakhtang Karseladze, who provided guidance to discipline his talent and slow down his impulsive tempo. The effect was immediate. Under Karseladze’s mentorship, Zaitsev learned to pair his natural creativity with greater practicality.

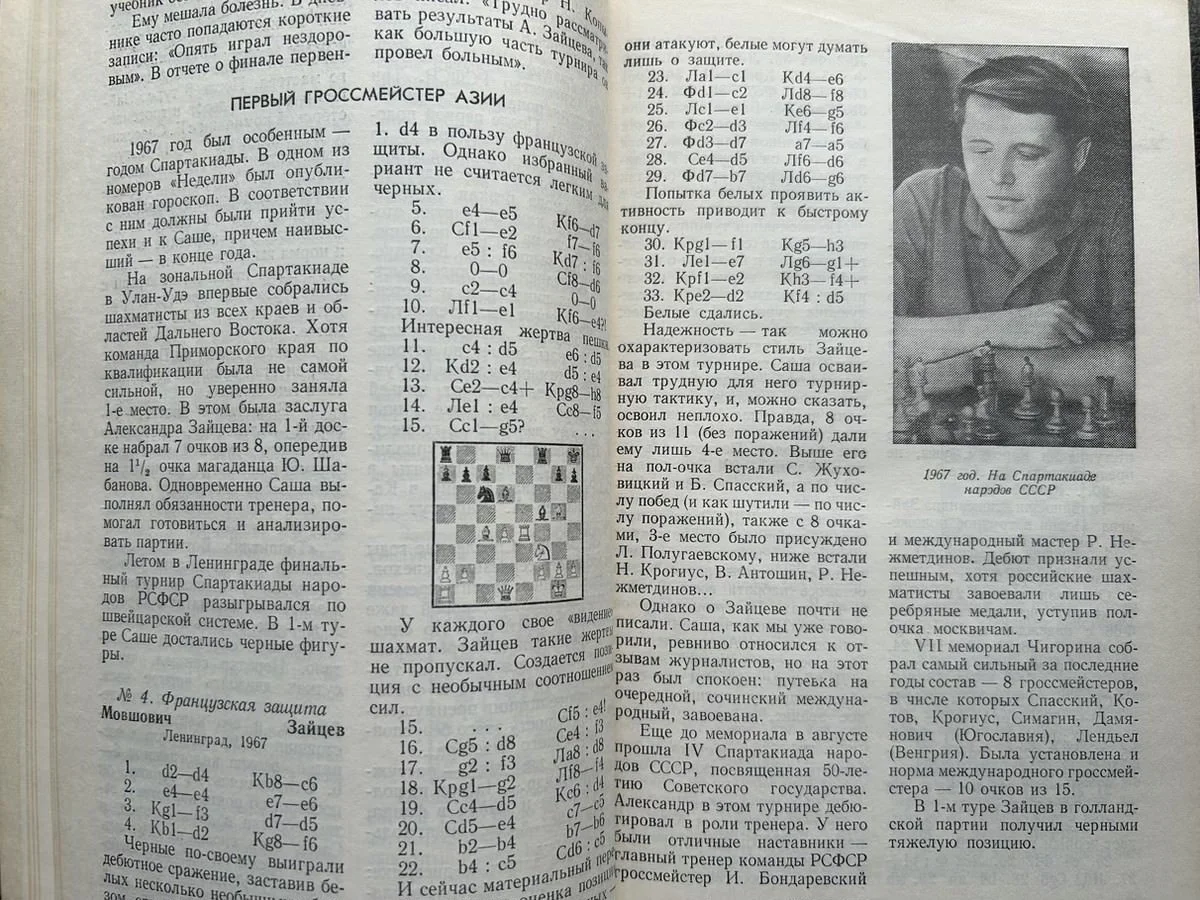

In 1965, Zaitsev fulfilled the norm for International Master, and two years later, he achieved his dream. At the prestigious 1967 Chigorin Memorial tournament in Sochi, the 32-year-old Zaitsev tied for first place in a strong field featuring Grandmasters like Boris Spassky, Nikolai Krogius, Leonid Shamkovich, and Vladimir Simagin. This result earned him the title of International Grandmaster by FIDE, making him the first chess grandmaster ever produced from the Soviet Far East (indeed, the first in all of Asia, as Soviet chess officials proudly noted). At the closing ceremony in Sochi, chess patron Vera Tikhomirova celebrated the milestone: “Our goal is achieved – Asia now has its first grandmaster!” Zaitsev’s success was hailed as a triumph for the remote provinces. Now, as one Soviet report put it, he stood “alone of his kind for thousands of kilometers” in his part of the world.

The 1969 USSR Championship

Zaitsev’s finest hour came in the 36th USSR Championship (Alma-Ata 1969), one of the strongest national championships ever. There, against an all-star field, Zaitsev delivered the performance of his life – tying for first place with Grandmaster Lev Polugaevsky, a future World Championship Candidate. Although Zaitsev narrowly lost the two-player playoff match (+1 −2 =3, score 2½–3½) to Polugaevsky and thus took the silver medal, his shared first place in such a legendary event stands as one of the great overachievements in Soviet championship history. Contemporary chess ranking metrics back up how strong Zaitsev was at his peak: the Chessmetrics historical rating site estimates his strength during this period to be equivalent to about 2660 ELO, placing him roughly among the world’s top 25 players in 1969.

More importantly, Zaitsev showed that he could go head-to-head with the very best players of his era. Over his career, he faced all the Soviet world champions except Botvinnik, and held his own remarkably well. He had an even lifetime score against both Tigran Petrosian and Boris Spassky, scored at least one victory over former world champion Vassily Smyslov, and was outscored only by Mikhail Tal and a young Anatoly Karpov. In one notable game at the Russian Championship in 1970, Zaitsev fearlessly entered a chaotic tactical battle with the rising star Karpov, even marching his king into the center of the board in a defiant display of ingenuity. Although Karpov eventually prevailed in that encounter (as he did in their overall score), Zaitsev’s fighting play left a strong impression. Few players outside the reigning elite could boast such a record against the Soviet chess titans of the 1960s.

A Bright Flame Cut Short

Throughout his life, Zaitsev quietly battled a serious health issue. He had suffered a severe infection in his leg as a small child (a bone inflammation around age 3), which left him with a permanent injury and a limp. For decades he endured chronic pain in that leg. The condition periodically affected his tournament play; long travel or lengthy games could become agonizing, but Zaitsev rarely complained and never let it diminish his love for chess. By 1971, however, the pain had worsened to the point that 36-year-old Zaitsev told his family he “could not endure it any longer”. That year, he elected to undergo a risky surgery to correct the problem finally. Tragically, the operation led to unexpected complications. He developed a post-surgical thrombosis (blood clot), and on October 31, 1971, Alexander Zaitsev died in the hospital in Vladivostok. He was only 36 years old.

Zaitsev’s sudden death stunned the Soviet chess world. He had just reached his prime as a grandmaster and was poised to be a fixture in top national competitions for years to come. Beyond his chess strength, he was universally liked for his genial personality and sportsmanship. Friends and colleagues remembered his creativity, charm, and the infectious enthusiasm he brought to any gathering. As GM Igor Zaitsev later wrote in tribute: “In my memory he will always remain a bright, cheerful person, whom I was used to seeing in the center of any chess gathering—lively, cheerful, full of stories. And at the board he was brilliant.”

Legacy of a Forgotten Artist

Alexander Zaitsev left behind relatively few games, but almost all of them sparkle. In his short career, he managed to produce a trove of innovative, beautiful games that players still marvel at today. His battles are filled with ideas that often feel ahead of their time, the kind of moves that seem obvious only after he has shown them. Soviet periodicals of the 1960s and early ’70s often spoke of Zaitsev in a tone reserved for a particular kind of player: the insider’s genius, the “master’s master” who was revered by his peers even if not widely known to the public.

Fifteen years after his death, in 1986, a collection of Zaitsev’s best games was finally published in Moscow (authored by Boris Archangelsky and Rudolf Kimelfeld). This slim volume containing Zaitsev’s sparkling combinations, deep positional insights, and memoirs from colleagues became something of a secret treasure among Soviet chess enthusiasts. It cemented Zaitsev’s status as one of those brilliant talents just outside the limelight of world champions. (See Pics)

Today, Alexander Zaitsev’s legacy stands as a reminder of the richness hidden in Soviet chess history. Beyond the famous World Champions and Candidates, there were brilliant minds like Zaitsev whose stories deserve to be remembered. He was one of those minds, a pioneer from the Far East, an innovator in chess theory, and a creative force gone far too soon.

Sources

Chess.com – “Remembering Alexander Zaitsev” (KingsBishop’s Blog, 2020): Brief biography and achievements of Alexander Zaitsev.

Encyclopedia of Primorye – “Первый международный гроссмейстер” (2011): Russian article on Zaitsev’s life and career, including Tal’s quote about their 1962 game and details on Zaitsev becoming the first Grandmaster of the Far East. https://alltopprim.ru/archives/1149

Ruchess.ru – Person of the Day (15 June 2025) – Alexander Zaitsev: A Russian Chess Federation tribute outlining Zaitsev’s development, coaching by Karseladze, major results (Sochi 1967, Alma-Ata 1968/69), health issues, and Igor Zaitsev’s reminiscence.

Primorsky Krai Public Library – “85 years since the birth of A.N. Zaitsev” (15 June 2020): Detailed Russian biography with quotes from Tal and Spassky, Zaitsev’s career highlights, style, and personality.

Archangelsky B.N. & Kimelfeld R.I. – Alexander Zaitsev (Moscow: Fizkultura i sport, 1986): A game collection and biographical monograph on Zaitsev. Annotation notes Zaitsev’s short but bright life and the many beautiful games he left behind. xchess.ru

Научно-популярное издание

Архангельский Борис Николаевич

Кимельфельд Рудольф Иосифович

АЛЕКСАНДР ЗАЙЦЕВ © Издательство «Физкультура и спорт», 1986 г. Thanks ;)