Grigory Levenfish: The Forgotten Champion of Soviet Chess

Grigory Yakovlevich Levenfish (1889–1961) was one of the great “could have been” talents of chess, a two-time Soviet champion and peer of future legends, yet fated to live in the shadows. In the 1920s and 1930s, he ranked among the world’s best, but politics and prejudice kept him from the opportunities his skill merited. His story is one of brilliance, resilience, and quiet dignity in the face of neglect. “He was a pure soul but also a tragic one, a genuine chess martyr,” remembered Fedor Bohatirchuk, Levenfish’s contemporary.

Early Brilliance in Imperial Russia

Levenfish’s chess journey began in the last years of the Russian Empire. Born in Piotrków, in the Russian-controlled Kingdom of Poland, he grew up in St. Petersburg and learned chess early from his father. By his early 20s, he had emerged as one of the country’s brightest talents. In 1909, the 20-year-old Levenfish won the St. Petersburg city championship, announcing himself as a force on the national scene. Soon after, he got a taste of elite international chess at the famed Carlsbad 1911 tournament. There, the 22-year-old scored a respectable 12/25, earning the German Chess Union’s Master title. Carlsbad was one of only two tournaments he would ever play outside Russia—the other being Baden-Baden 1925. A rare group photograph from Carlsbad, 1911, shows the young Levenfish seated among the giants of that era, an international stage on which he would unfortunately never again regularly appear.

The upheavals of World War I and the Russian Revolution put Levenfish’s chess ambitions on hold. He qualified as a chemical engineer and, by his own account, endured personal tragedy (his wife died in 1917) and years of struggling for basic work. Chess had to take a back seat during those turbulent times. It was not until the early 1920s, with Soviet chess institutions taking shape, that Levenfish returned to competitive form. He quickly reestablished himself among the top Soviet players, winning the Leningrad Championship in 1922, 1924, and 1925. In the new USSR chess scene—where many pre-Revolution masters had emigrated or were no longer in the country (Alekhine, Bogoljubov, Nimzowitsch, etc.)—Levenfish was one of the few representatives of that older generation still in the Soviet Union. He carried the torch for the pre-Revolution masters who stayed behind, proving that their talent was undimmed by years of isolation.

Triumphs on the National Stage

Levenfish’s finest years arrived in the mid-1930s, when he finally earned the titles and recognition at home that his talent had long warranted. He had threatened greatness earlier—finishing 3rd in the inaugural Soviet Championship of 1920 and 2nd in 1923—but his true breakthroughs came more than a decade later. In 1934, at age 44, Levenfish tied for first in the Soviet Championship, sharing the title with Ilya Rabinovich and becoming, at last, an official national champion. Three years later, he reached an even higher peak. In 1937, in Tbilisi, Levenfish won the 10th Soviet Championship outright, securing his second national title. In an era when a new generation of young Soviet stars was rapidly ascending, the nearly 50-year-old Levenfish demonstrated that mastery, experience, and perseverance could still triumph.

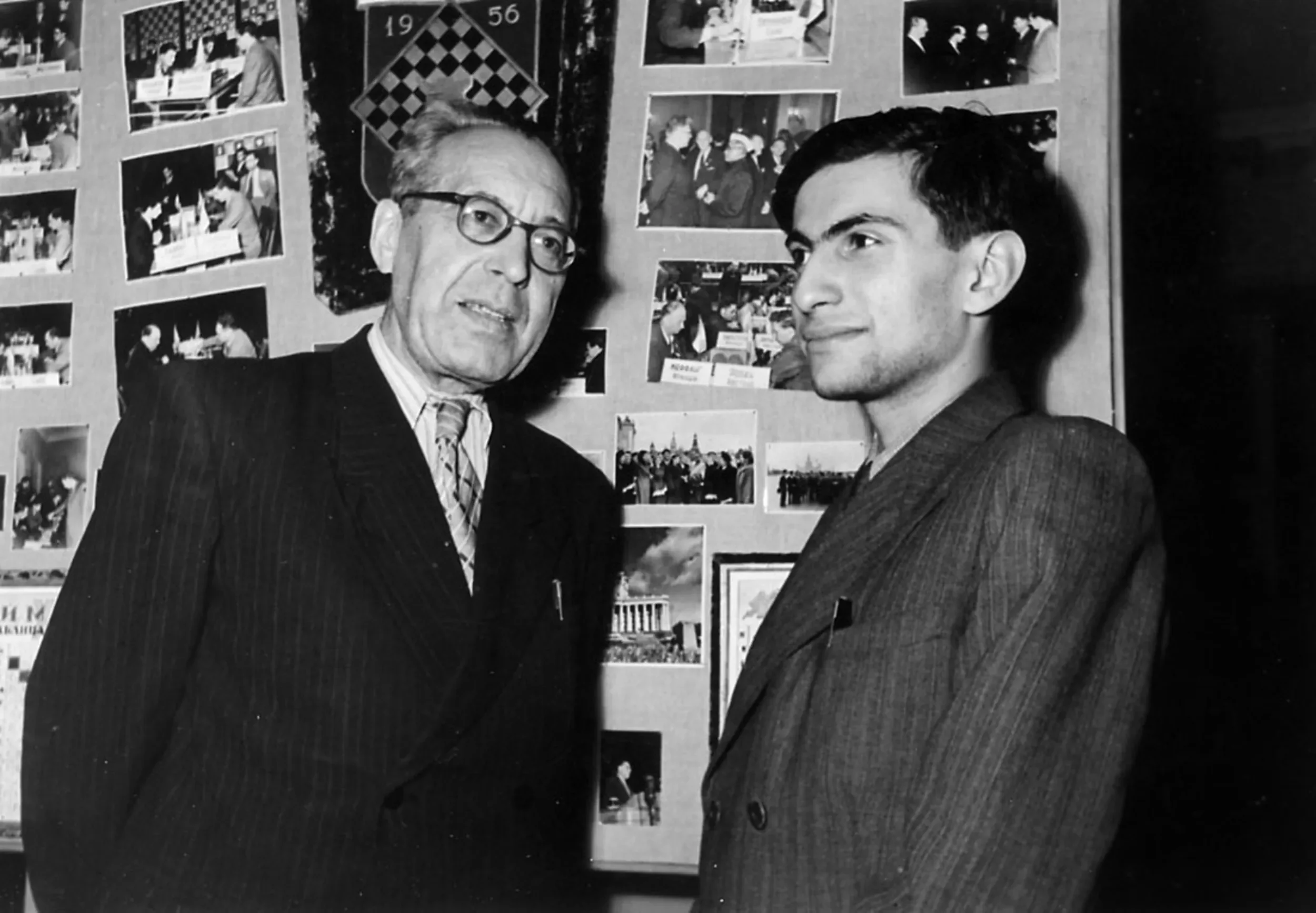

As reigning champion of the USSR, he soon faced the next major test: a title match against the rising Soviet prodigy Mikhail Botvinnik. Botvinnik—22 years younger and already the favored son of the Soviet chess establishment—was widely expected to dominate. Their match, held in January–February 1937, became a clear clash of generations. Levenfish began superbly, taking an early lead and startling observers who anticipated a smooth Botvinnik victory. But as the contest wore on, Botvinnik’s precise, scientific style asserted itself. After ten intense games, Botvinnik won by 6½–4½. Though defeated, Levenfish had pushed the rising star far harder than the chess authorities had predicted. A well-known photograph from the match shows Levenfish (seated left) facing Botvinnik across the board—a striking visual of the old guard meeting the new.

Levenfish had already proven himself on the international stage. In the strong 1925 Moscow tournament, he famously defeated former world champion Emanuel Lasker and drew with reigning champion José Raúl Capablanca—rare accomplishments in that era. His competitive showing against Botvinnik in 1937 only reinforced his elite standing. As chess historian Andrew Soltis has noted, by 1938 Levenfish ranked roughly world #9 on modern Chessmetrics calculations, behind only the eight players who appeared at the legendary AVRO 1938 tournament. Under ordinary circumstances, the Soviet champion would have joined that field. But for reasons rooted in politics rather than chess, the Soviet authorities chose not to send him.

Denied the World Stage

Tragically, “normal circumstances” did not apply to Levenfish’s Soviet reality. Despite being the reigning USSR champion, he was never given the opportunity to play in the 1938 AVRO tournament in the Netherlands—one of the strongest and most important tournaments ever held. Although the AVRO organizers requested that the Soviet Union send its top representative, the Soviet sports authorities selected only Botvinnik. Levenfish, whose recent achievements made him the logical and deserving nominee, was left behind. What should have been the crowning moment of his career became instead a painful reminder of how politics, not merit, determined opportunity.

For Levenfish, the disappointment was profound and enduring. He spoke candidly about how deeply the decision wounded him: “I considered that my victories in the ninth and tenth USSR Championships and the drawn match against Botvinnik gave me the right to participate in the AVRO tournament,” he later wrote. “However, despite my hopes, I was not sent to this event. My situation could be defined as a moral knock-out. All my efforts of the preceding years had been in vain. I felt confident in my powers and would undoubtedly have fought honorably in the tournament.” He summarized the devastation even more starkly in his memoir: “Contrary to my hopes, I was not sent to that tournament… I gave up my chess career as lost.”

This decision by the Soviet authorities marked the beginning of the end of Levenfish’s top-level career. Denied the chance to measure himself against Capablanca, Alekhine, Keres, and the rest of the world’s elite at AVRO, his motivation understandably collapsed. He continued to play in Soviet competitions for several more years, but after 1938 his results slipped noticeably. The spark of ambition had been extinguished. Botvinnik, meanwhile, went to AVRO in Levenfish’s place, tied for 3rd, and from that point onward received the full institutional backing of the Soviet chess apparatus. Levenfish, by contrast, receded into the margins—his prime years squandered by a lack of opportunity that had nothing to do with chess and everything to do with politics.

The Outsider in Soviet Chess

Levenfish’s fate was not just a matter of one tournament. It was emblematic of how the Soviet chess establishment treated him. He was “virtually ignored by the Soviet chess authorities,” as one account dryly notes. While talents like Botvinnik (a loyal communist 22 years younger) were nurtured, Levenfish was seen as part of the “old guard” – talented but not politically ideal. He never joined the Communist Party, and he had an independent, sometimes sarcastic personality that did not ingratiate him with officials. As a result, Levenfish was one of the very few top Soviet masters of his generation who never received the stable, government-backed salary that defined professional chess life in the USSR. In an era when being a “professional” chess player meant being placed on the state payroll, Levenfish was largely excluded. He lived in poverty, renting a poorly heated single room in a communal apartment. Contemporary master Yakov Neishtadt recalled visiting Levenfish in those years: “He lived in great poverty, in a room with firewood heating in a communal flat… He was very hard-up, but he never complained to anyone about anything.” That stoic refusal to beg for pity perhaps made it easier for officials to continue overlooking him.

Apart from the financial hardship, Levenfish was isolated competitively. Other pre-revolution masters who might have been his natural rivals had long left the USSR (Alekhine settled in France, Bogoljubov in Germany, etc.). Deprived of chances to play internationally, Levenfish could only compete against countrymen and watch from afar as global chess evolved. It is telling that nearly all of his games against reigning world champions took place on Soviet soil – yet his results in those encounters were impressive. Over his career, he scored wins or draws against five world champions: he beat Emanuel Lasker in 1925, fought José Raúl Capablanca to a draw in 1925, held his own in his limited meetings with Alexander Alekhine, and even at age 60 defeated Vassily Smyslov (who was about to challenge for the world title) in the USSR Championship of 1949. Against Botvinnik, across their competitive encounters during Levenfish’s prime years, he scored only a small minus – a highly respectable showing against the future world champion. Such statistics underline that Levenfish had the skill to belong in the highest company, even if the world was never allowed to witness it directly.

Levenfish’s status as an “outcast” in Soviet chess was not only due to politics, but also partly to his own temperament. He was a proud man of the old school – “an aristocrat by spirit and education,” as described by GM Genna Sosonko. He spoke several languages, played tennis, enjoyed fine wine, and had the bearing of a pre-revolution intellectual. This made him something of an alien figure in the more proletarian, state-sponsored Soviet chess circles. To younger Soviet players, Levenfish’s erudition and wit were memorable. Viktor Korchnoi, who as a teenager took lessons from Levenfish, recalled his mentor vividly: “He gave me the impression of being a very cultured man, witty and developed in all respects. I realized that this was a man from another world… When I got to know Botvinnik and began comparing, the comparison was not in favor of Botvinnik. Next to Levenfish, [Botvinnik] seemed a shallow person… Levenfish was an intellectual by blood and by pre-Revolutionary education.” This sharp observation from Korchnoi highlights the divide: Botvinnik was a model Soviet intellectual, but Levenfish was a true old-world intellectual who couldn’t (and wouldn’t) conform.

Unsurprisingly, Levenfish could be blunt and “prickly” in speech, which did not help his political fortunes. “He possessed an enormous natural talent, and he was an outstanding player,” admitted Boris Spassky, who knew Levenfish later in life. “The fact that he was harsh, with a prickly tongue – well, how could he not be prickly, when Soviet life had practically destroyed him? But at heart he was responsive and very subtle.” Those who became close to Levenfish found a kind, refined soul beneath the crusty exterior. But to Soviet officials, his sarcasm and lack of deference marked him as a persona non grata. Thus, throughout the 1930s, even as Levenfish won championships and represented the pinnacle of Soviet chess skill, he was treated as an inconvenient relic – someone to be respected for his results, perhaps, but not celebrated or supported in proportion to his achievements.

Mentor, Author, and Endgame Virtuoso

World War II interrupted chess once more, and again Levenfish dutifully served his country outside the chessboard – this time as an engineer in charge of a glass factory evacuated to Penza. He nearly lost his life during the war; at one point, he had to trek 18 kilometers in sub-zero cold, an ordeal from which his health “never fully recovered.” After the war, Levenfish – now in his late 50s – never returned to active tournament play with the same intensity. However, he continued to contribute to Soviet chess in meaningful ways. Settling in Leningrad, he became the head instructor at the city’s Pioneer Palace chess club, training promising youth. Among his pupils were two boys who would later become legends: Boris Spassky and Viktor Korchnoi. Through these students, Levenfish’s knowledge and fighting spirit were passed down to the next generation. Spassky later remembered how Levenfish always remained generous in sharing his chess wisdom, even as life wore him down. A poignant anecdote comes from 1961, when Spassky happened to encounter Levenfish on a Moscow street shortly before the old master’s death: Levenfish, pale and gaunt from a recent hospital visit, walked with his head in his hands, the image of a once-great fighter now in decline. A few days later, on February 9, 1961, Grigory Levenfish passed away at age 71. It was said that Spassky was one of the last people to speak with him. Soviet chess had lost a living link to its pre-Revolution roots.

If Levenfish was denied recognition as a player, he found a different kind of immortality through chess writing and theory. He was a renowned expert on the chess endgame – especially rook endgames, the most demanding of all. In the 1950s, Levenfish poured his lifelong endgame analysis into a manuscript on rook endings. Near the end of his life, he brought a massive stack of papers to Vassily Smyslov (who was not only a world-class player but also a fine endgame analyst) and asked him to check the analysis. Smyslov did so, and with only minor corrections, the work was published in 1957 as Theory of Rook Endings (Teoriya ladeynykh okonchaniy). Out of respect, Smyslov was listed as co-author, though he later admitted that “all of the hard work was carried out by [Levenfish].” This book – eventually translated into English as Rook Endings – became a classic, studied by generations of chess players. One of Levenfish’s most famous victories, his win against Emanuel Lasker in Moscow 1925, was not a rook endgame but it showcased the same clarity and precision that defined his analytical style. He annotated this and many other endings and near-endings in his work. Levenfish’s legacy thus lives on in every carefully played rook ending – his analytical labors still guide masters decades later.

Levenfish also made his mark in the realm of chess openings. An aggressive line of the Sicilian Defense, the move 6.f4 against the Dragon variation, is known as the Levenfish Attack – reflecting ideas he pioneered in his games. Every time a modern player launches an all-out kingside pawn storm in the Sicilian Dragon, they pay an unconscious homage to Levenfish’s fighting spirit. In addition, Levenfish co-authored (with Peter Romanovsky) one of the first great Soviet tournament books, covering the 1927 New York World Championship match between Capablanca and Alekhine. And, not least, he left behind a memoir. Fittingly – and poignantly – Levenfish titled his autobiography Izbrannye partii i vospominaniya (Selected Games and Memoirs). It was published posthumously in 1967. Although the modern phrase “Soviet outcast” has become associated with his story, it was not part of the book’s original title – but it captures how history has come to view him: a great master who never received his due.

Legacy and Inspiration

Grigory Levenfish’s life in chess is a study in contrasts: extraordinary talent and achievements, met with indifference or even obstruction by the powers of his day. On paper, his accomplishments were remarkable – double Soviet champion, holder of wins against some of the strongest players of all time, co-author of seminal chess works. Yet during his lifetime he never enjoyed the fame or support that many of his contemporaries did. It took decades for chess historians to truly appreciate Levenfish’s contributions. Today, however, we recognize him as one of the strongest players of the 1930s who never got a shot at the World Championship, largely due to circumstances beyond his control. His chess strength was such that even world champions had to respect him – and he scored notable individual successes against several of them, including Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Smyslov, and Botvinnik. These encounters show that Levenfish belonged in the highest company, even if the world was not permitted to see his full potential.

Perhaps more importantly, Levenfish’s story resonates as a human tale of perseverance. He remained true to himself – independent in thought, never asking for favors – and continued to love chess even when it could not love him back in the form of recognition. Genna Sosonko wrote that grandmasters who knew Levenfish spoke of “a man of integrity and independence, who never complained about his difficult living conditions.” Indeed, Levenfish retained his dignity to the very end. In his later years, he could often be found at the chess club or café, impeccably dressed, analyzing positions or playing cards (another passion), always ready with a sharp remark or a bit of dry humor. To the young Soviet talents coming up, he was a living link to a lost world – a reminder that there were great masters before the Soviet era who deserved honor.

Levenfish’s legacy today is secure among chess connoisseurs, even if his name is not as universally known as some of his rivals. Every chess player who consults Levenfish & Smyslov’s Rook Endings to learn a tricky endgame, or who surprises their opponent with 6.f4 in the Dragon Sicilian, is keeping a part of Levenfish alive. His games – once buried in old Soviet bulletins – are now studied and admired for their classical clarity and endgame virtuosity. One of his wins from the 1937 Botvinnik match, for example, is hailed by commentators as one of the best games of that era, showcasing Levenfish’s positional mastery and fighting spirit.

In remembering Grigory Levenfish, we honor not only a great chess player but also the principle that no legacy should be forgotten. His life reminds us that success isn’t always measured by titles alone; it is often defined by the respect earned from peers, the knowledge passed to students, and the inspiration given to future generations. Levenfish may have been a “runner-up” in the annals of Soviet chess – overshadowed by Botvinnik and ignored by officials – but his contributions were runner-up to none. Today, thanks to efforts by chess historians and enthusiasts, Levenfish is finally getting his due as a Soviet chess hero in his own right. His story of talent thwarted but never extinguished continues to educate and inspire. In the end, Grigory Levenfish’s legacy lives on – a testament to a true chess artist who shone brightly, even from the shade. No great player’s legacy, however overlooked in its time, is ever truly lost.