Efim Bogoljubow: Tournaments, Internment and Blindfold Battles

Efim Bogoljubov was one of the most imaginative chess players of the early 20th century. Born in 1889 in what is now Ukraine, he became a grandmaster who first represented the Russian Empire/Soviet Union and later Germany. Many fans remember him for his creative attacking style and his sense of humor that produced the quote: “When I play White, I win because I am White. When I play Black, I win because I am Bogoljubov.”

A Fateful Tournament in Germany

Bogoljubov’s life changed dramatically at the 19th German Chess Federation congress in Mannheim in July–August 1914. During the event, World War I broke out, and the German authorities arrested the eleven Russian participants, including Bogoljubov and Alexander Alekhine. After short internments in Mannheim, Ludwigshafen, and Rastatt, Bogoljubov was moved to the Black‑Forest village of Triberg. The conditions were relatively mild—he and the other Russian masters were allowed to play tournaments and even met local residents. It was in Triberg that he met Frieda Kaltenbach, a schoolteacher’s daughter; they married in 1920 and later had two daughters.

After the war, Bogoljubov chose to stay in Germany. He quickly established himself as a leading player on the tournament scene. In 1922, he won the international tournament at Bad Pistyan, finishing first with 15 points out of 18—half a point ahead of Alekhine and Rudolf Spielmann. Two years later, he returned to Russia to compete in the Soviet Championship, winning in both 1924 and 1925, and took first place at the prestigious Moscow International Tournament ahead of former world champions Emanuel Lasker and José Raúl Capablanca. That same year, he also won the German championship (Deutsche Meisterschaft (24. DSB‑Kongress, Meisterturnier)) in Breslau, making him the only player ever to hold both the Soviet and German championships in the same year. These achievements cemented his reputation as Germany’s top player and opened opportunities for future world championship matches.

Life in Captivity and Blindfold Games

The tribulations of internment did not dull Bogoljubov’s enthusiasm. He spent hours playing blindfold chess with Alekhine during their incarceration. These games sharpened both players’ tactical vision and forged a friendly rivalry. After his release, Bogoljubov embarked on a series of victories in Germany and Sweden, beating the positional genius Aron Nimzowitsch and drawing with his former jail‑mate Alekhine.

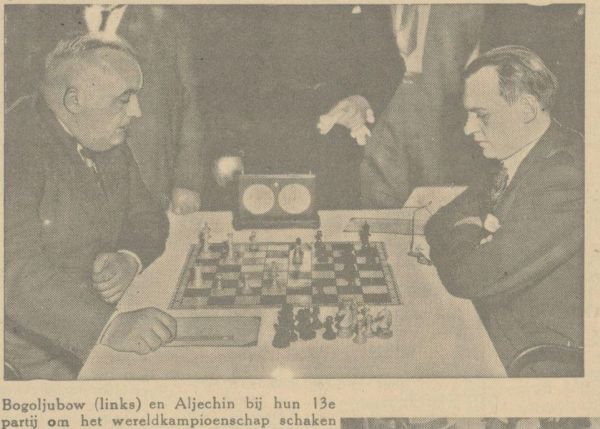

Bogoljubov’s blindfold sessions with Alekhine returned to prominence during the 1920s. In 1928, he challenged Alekhine and became a German citizen on November 2, 1929. The two had “played countless blindfold games during their internment after Mannheim 1914," and their rivalry led to two world championship matches. The first, held in Germany and the Netherlands in 1929, saw Alekhine emerge victorious; the rematch in 1934, played across twelve German cities, ended the same way. While Bogoljubov never won the title, these matches are remembered for their fighting spirit and spectacular combinations.

Legacy and later years

Despite political upheavals, Bogoljubov remained a prolific player and trainer. He won numerous German tournaments throughout the 1930s, represented Germany at the 1931 Chess Olympiad, and later coached the national team. During the Nazi era, he faced discrimination because he was not considered “Aryan,” yet he continued to mentor rising talents and contribute to chess literature. After World War II, he was sidelined by Soviet officials and was not awarded the grandmaster title until 1951. He died in Triberg in 1952, leaving behind a body of inventive games and a distinctive contribution to opening theory, most famously the Bogoljubov Defence (Bogo-Indian).

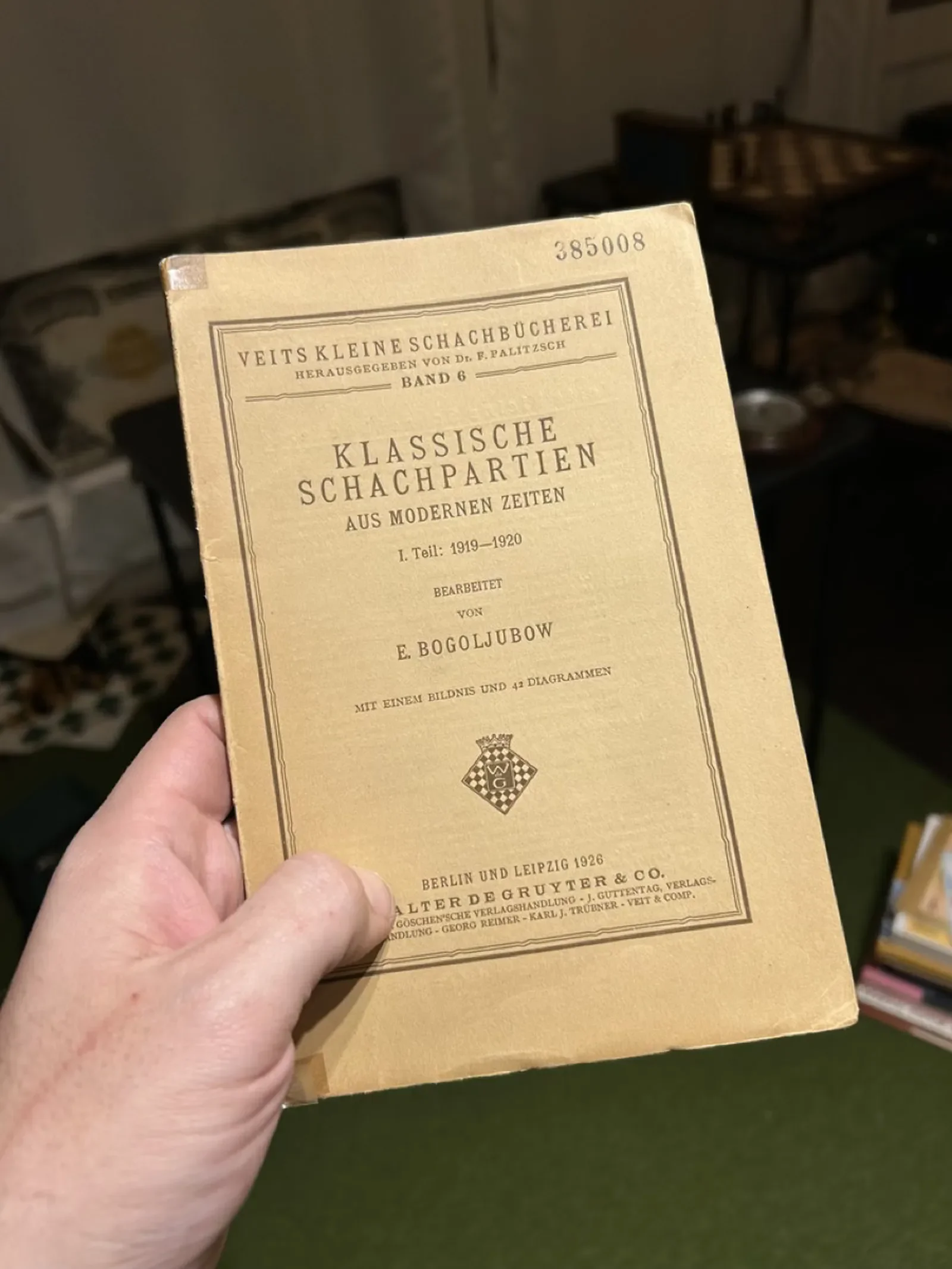

He also contributed to chess literature, editing Klassische Schachpartien aus modernen Zeiten. I. Teil: 1919–1920 (Veits kleine Schachbücherei, Band 6; Berlin und Leipzig: Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1926), a compact selection “mit einem Bildnis und 42 Diagrammen.”

(German‑language editions use the spelling Bogoljubow.)

Between his internment and title matches, Bogoljubov also wrote. This slim 1926 de Gruyter volume—Klassische Schachpartien aus modernen Zeiten—reveals his editorial voice and shows how German readers encountered “Bogoljubow” in print.

Bogoljubov’s journey from interned player to world‑championship challenger captures the drama and resilience of early 20th‑century chess. His games remain enjoyable studies for anyone who loves dynamic, imaginative play, and his life story adds depth to the rich tapestry of Soviet and German chess history.